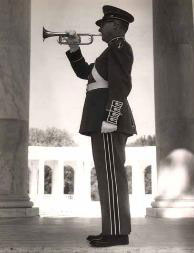

Taps

Of all the military bugle calls, none is so

easily recognized or more apt to render

emotion than the call Taps. The melody is both eloquent and haunting and the

history of its origin is interesting and somewhat clouded in controversy. In

the

British Army, a similar type call known as Last Post has been sounded over

soldiers'

graves since 1885, but the use of Taps is unique to the

since the call is sounded at funerals, wreath-laying and memorial services.

Taps began as a revision to the signal for

Extinguish Lights (Lights Out) at the end of the day. Up until the Civil War,

the infantry call for Extinguish Lights was the one set down in Silas Casey's

(1801-1882) Tactics, which had been borrowed from the French. The music for

Taps was adapted by Union General Daniel Butterfield for his brigade (Third

Brigade, First Division, Fifth Army Corps, Army of the

Of all the military bugle calls, none is so

easily recognized or more apt to render

emotion than the call Taps. The melody is both eloquent and haunting and the

history of its origin is interesting and somewhat clouded in controversy. In

the

British Army, a similar type call known as Last Post has been sounded over

soldiers'

graves since 1885, but the use of Taps is unique to the

since the call is sounded at funerals, wreath-laying and memorial services.

Taps began as a revision to the signal for

Extinguish Lights (Lights Out) at the end of the day. Up until the Civil War, the

infantry call for Extinguish Lights was the one set down in Silas Casey's

(1801-1882) Tactics, which had been borrowed from the French. The music for

Taps was adapted by Union General Daniel Butterfield for his brigade (Third

Brigade, First Division, Fifth Army Corps, Army of the

The highly romantic account of how Butterfield

composed the call surfaced in 1898 following a magazine article written that

summer. The August, 1898 issue of Century Magazine contained an article

called "The Trumpet in Camp and

"In speaking of our trumpet calls I

purposely omitted one with which it seemed most appropriate to close this

article, for it is the call which closes the soldier's day... Lights Out. I have not been able to trace this call to

any other service. If it seems probable, it was original with Major

Seymour, he has given our army the most beautiful of all trumpet-calls."

Kobbe was using as an authority the Army drill manual on infantry

tactics prepared by Major General Emory Upton in 1867 (revised in 1874). The

bugle calls in the manual were compiled by Major (later General) Truman Seymour

of the 5th U.S. Artillery. Taps was called Extinguish Lights in these manuals

since it was to replace the "Lights Out" call disliked by

Butterfield. The title of the call was not changed until later, although

other manuals started calling it Taps because most

soldiers knew it by that name. Since

Norton wrote:

"Chicago, August 8, 1898

I was much interested in reading the article by Mr. Gustav Kobbe,

on the Trumpet and Bugle Calls, in the August Century. Mr. Kobbe says that he has been unable to trace the origin of

the call now used for Taps, or the Go to Sleep, as it is generally called by

the soldiers. As I am unable to give the origin of this call, I think

the following statement may be of interest to Mr. Kobbe

and your readers... During the early part of the Civil War I was bugler at the

Headquarters of Butterfield's Brigade, Morell's

Division, Fitz-John Porter's Corps, Army of the

One day, soon after the seven days battles on the Peninsula, when

the Army of the Potomac was lying in camp at Harrison's Landing, General Daniel

Butterfield, then commanding our Brigade, sent for me, and showing me some

notes on a staff written in pencil on the back of an envelope, asked me to

sound them on my bugle. I did this several times, playing the music as written.

He changed it somewhat, lengthening some notes and shortening others, but

retaining the melody as he first gave it to me. After getting it to his

satisfaction, he directed me to sound that call for Taps thereafter in place of

the regulation call. The music was beautiful on that still summer night, and

was heard far beyond the limits of our Brigade. The next day I was visited by

several buglers from neighboring Brigades, asking for copies of the music which

I gladly furnished. I think no general order was issued from army headquarters

authorizing the substitution of this for the regulation call, but as each

brigade commander exercised his own discretion in such minor matters, the call

was gradually taken up through the Army of the

-Oliver W. Norton

The

editor did write to Butterfield as suggested by Norton. In answer to the

inquiry from the editor of the Century, General Butterfield writing from

Gragside, Cold Spring, on

"I recall, in my dim memory, the substantial truth of the

statement made by Norton, of the 83rd

The call of Taps did not seem to be as smooth, melodious and musical as it

should be, and I called in some one who could write music, and practiced a

change in the call of Taps until I had it suit my ear, and then, as Norton

writes, got it to my taste without being able to write music or knowing the

technical name of any note, but, simply by ear, arranged it as Norton

describes. I did not recall him in connection with it, but his story is substantially

correct. Will you do me the favor to send Norton a copy of this letter by your

typewriter? I have none."

On

the surface, this seems to be the true history of the origin of Taps. Indeed,

the many articles written about Taps cite this story as the beginning of

Butterfield's association with the call. Certainly, Butterfield never went out

of his way to claim credit for its composition and it wasn't until the

Century article that the origin came to light.

There are however, significant differences in Butterfield's and Norton's

stories. Norton says that the music given to him by Butterfield that

night was written down on an envelope while Butterfield wrote that he could not

read or write music! Also Butterfield's words seem to suggest that he was

not composing a melody in Norton's presence, but actually arranging or revising

an existing one. As a commander of a brigade, he knew of the bugle calls

needed to relay troop commands. All officers of the time were required to

know the calls and were expected to be able to play the bugle. Butterfield

was no different - he could sound the bugle but could not read music. As

a colonel of the 12th NY Regiment, before the war, he had ordered his men to be

thoroughly familiar with calls and drills.

What

could account for the variation in stories? My research shows that Butterfield

did not compose Taps but actually revised an earlier bugle call. The fact is

that Taps existed in an early version of the call Tattoo. As a signal for end

of the day, armies have used Tattoo to signal troops to prepare them for

bedtime roll call. The call was used to notify the soldiers to cease the

evening's drinking and return to their garrisons. It was sounded an hour before

the final call of the day to extinguish all fires and lights. This early

version is found in three manuals - the Winfield Scott (1786-1866) manual of

1835, the Samuel Cooper (1798-1876) manual of 1836 and the William Gilham (1819?-1872) manual of 1861. This call, referred to

as the Scott Tattoo, was in use from 1835-1860. A second version of Tattoo came

into use just before the Civil War and was in use throughout the war replacing

the Scott Tattoo.

The

fact that Norton says that Butterfield composed Taps cannot be questioned. He

was relaying the facts as he remembered them. His conclusion that Butterfield

wrote Taps can be explained by the presence of the second Tattoo. It was most

likely that the second Tattoo, followed by Extinguish Lights (the first eight

measures of today's Tattoo), was sounded by Norton

during the course of the war.

It seems possible that these two calls were sounded to end the soldier's day on

both sides during the war. It must therefore be evident that Norton did not

know the early Tattoo or he would have immediately recognized it that evening

in Butterfield's tent. If you review the events of that evening, Norton came

into Butterfield's tent and played notes that were already written down on an

envelope. Then Butterfield, "changed it somewhat,

lengthening some notes and shortening others, but retaining the melody as he

first gave it to me." If you compare that statement while

looking at the present day Taps, you will see that this is exactly what

happened to turn the early (Scott) Tattoo into Taps.

Butterfield, as stated above, was a Colonel before the War and in General Order

No. 1 issued by him on December 7, 1859 had the order: "The Officers

and non-commissioned Officers are expected to be thoroughly familiar with the

first thirty pages, Vol. 1, Scott's Tactics, and ready to answer any

questions in regard to the same previous to the drill above ordered."

Scott's Tactics include the bugle calls that Butterfield must have known

and used. If Butterfield was using Scott's Tactics for drills,

then it is feasible that he would have used the calls as set in the manual.

Lastly, it is hard to believe that Butterfield could have composed anything

that July in the aftermath of the Seven Days battles which saw the Union Army

of the

In

the interest of historical accuracy, it should be noted that General

Butterfield did not compose Taps, rather that he

revised an earlier call into the present day bugle call we know as Taps. This

is not meant to take credit away from him.

Following

the Peninsular Campaign, Butterfield served at 2nd

Butterfield died in 1901. His tomb is the most ornate in the cemetery at

How

did the call become associated with funerals? The earliest official reference

to the mandatory use of Taps at military funeral ceremonies is found in the

U.S. Army Infantry Drill Regulations for 1891, although it had doubtless been

used unofficially long before that time, under its former designation

Extinguish Lights.

The first sounding of Taps at a military funeral is commemorated in a stained

glass window at The Chapel of the Centurion (The Old Post Chapel) at

The site where Taps was born is also commemorated by a monument located on the

grounds of Berkeley Plantation, Virginia. This monument to Taps was erected by

the Virginia American Legion and dedicated on

Other

stories of the origin of Taps exist. A popular, yet false, one is that of a

Northern boy who was killed fighting for the south. His father, Robert Ellicombe, a Captain in the Union Army, came upon his son's

body on the battlefield and found the notes to Taps in a pocket of the dead boy's

Confederate uniform. He had the notes sounded at the boy's funeral. There is no

evidence to back up the story or the existence of a Captain Ellicombe.

Why

the name Taps? The call of Tattoo was used in

order to assemble soldiers for the last roll call of the day. Tattoo may have

originated during the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) or during the wars of King

William III during the 1690s. The word tattoo in this usage is derived from the

Dutch tap (tap or faucet) and toe (to cut off). When it was time to cease

drinking for the evening and return to the post, the provost or Officer of the

Day, accompanied by a sergeant and drummer, would go through the town beating

out the signal. As far as military regulations went, there was a prescribed

roll call to be taken "at Taptoe time" to

ensure that all the troops had returned to their billets. It is possible

that the word Tattoo became Taps. Tattoo was also called Tap-toe and as is true

with slang terms in the military, it was shortened to Taps.

The other, and more likely, explanation is that the name Taps was borrowed from

a drummer's beat. The beating of Tattoo by the drum corps would be followed by

the Drummer of the Guard beating three distinct drum taps at four count

intervals for the military evolution Extinguish Lights. During the

American Civil War, Extinguish Lights was the bugle call used as the final call

of the day and as the name implies, it was a signal to extinguish all fires and

lights. Following the call, three single drum strokes were beat at four-count

intervals. This was known as the "Drum Taps" or in common usage of

soldiers "The Taps" or "Taps." There are many

references to the term "Taps" before the war and during the conflict,

before the bugle call we are all familiar with came into existence. So the drum

beat that followed Extinguish Lights came to be called "Taps" by the

common soldiers and when the new bugle call was created in July 1862 to replace

the more formal sounding Extinguish Lights, (the one Butterfield disliked), the

bugle call also came to be known as "Taps."

The new bugle signal (also known as "Butterfield's Lullaby") is

called "Taps" in common usage because it is used for the same purpose

as the three drum taps. However the U.S. Army still called it Extinguish Lights

and it did not officially change the name to Taps until 1891.

As

soon as Taps was sounded that night in July 1862, words were put with the

music. The first were, "Go To Sleep, Go to Sleep."

As the years went on many more versions were created. There are no official

words to the music but here are some of the more popular verses:

Day is done, gone the sun,

From the hills, from the lake,

From the sky.

All is well, safely rest,

God is nigh.

Fades the light; And afar

Goeth day, And the stars

Shineth bright,

Fare thee well; Day has gone,

Night is on.

Thanks and praise, For our days,

'Neath the sun, Neath the stars,

'Neath the sky,

As we go, This we know,

God is nigh.

As

with many other customs, this solemn tradition continues today. Although

Butterfield merely revised an earlier bugle call, his role in producing those

twenty four notes gives him a place in the history of music as well as the

history of war.

REFERANCE:

INFO FROM..THE HISTORY OF TAPS; http://www.tapsbugler.com/24NotesExcerpt/Page1.html

Jari A. Villanueva is a bugler and bugle historian. A graduate of the Peabody Conservatory and Kent State University, he was the curator of the Taps Bugle Exhibit at Arlington National Cemetery from 1999-2002. He has been a member of the United States Air Force Band since 1985 and is considered the country's foremost authority on the bugle call of Taps.

His website, http://www.tapsbugler.com includes a history of Taps, performance information and guidelines for funerals, finding buglers for sounding calls, many photos of bugles and buglers, music for bugle calls, stories and myths about Taps, Taps at the JFK funeral, ordering his 60 page booklet on Taps (24 Notes That Tap Deep Emotions) and many links to bugle related sites. Jari is also working on book on the History of Bugle Call in the United States Military.